By Wolfgang Kapfhammer (LMU München)

“Nobody works out of love!” (Ezequiel)

„Ninguem trabalha por amor!“ a somewhat frustrated Ezequiel[1] snapped, as we – Ulrike Prinz, an anthropologist and journalist and I – sat amidst the ruins of a place that once has been the flagship of an Indigenous enterprise which commercializes forest products of the Sateré-Mawé, an Indigenous ethnic group on the Lower Amazon in Brazil. Among a dozen or so forest products the business primarily sells guaraná (Paullinia cupana) to European Fair Trade distributors (Kapfhammer and Winder, 2020). His frustration certainly had to do with the decline of the lodge and its forest garden, and also with the fact that he has been once again abandoned by his staff in the near-by city of Parintins. His staff had run away to Manaus taking a good deal of the project’s money with them. So he was understandably a bit unnerved when I insisted on asking him probing questions about the transformation of human–environment relations in the context of the Fair Trade enterprise.

Instead of providing some florid Indigenous nature philosophy Ezequiel gave us a lesson in his version of Weberian spirit of capitalism. While I hoped for narratives of reclaimed animism as incentive to engage in forest gardens, he grudgingly acknowledged that it isn’t Mother Earth but money that makes capitalism run and that it cannot be different in the Terra Indígena of the Sateré-Mawé. „If you don’t put money to the front, nobody will take interest into the project. Nobody works out of love! Love for the forest, love for your neighbor. Nobody!“ Then he contextualized his insights by explaining how monetizing Indigenous territories works. Once, an imagined past of largely auto-sufficient subsistence combined with diversified extractivism in exchange for industrial goods gave way to an increasing assistentialism by government organizations like FUNAI[2]. Governmental guardianship went along with a profound mental and habitual transformation which furthered materialistic expectations, while at the same time ruining auto-sufficient productivity. The progeny of the diligent gardeners and collectors now had „lost their spirit of production“ (espíritu de produção) preferring to go down the river to beg resources (food, gasoline etc.) from the local political authorities. In Ezequiel’s eyes it is exactly this system of neo-colonial dependency, the commercial enterprise has to compete with. Although the products of the project (guaraná, copaiba, andiroba, rosewood and many others) achieve a much higher price as on the local market, one has to invest a lot of working hours into a forest garden and is also compelled to strictly follow the specifications of the protocolo, which defines the standards for certified Fair Trade produce on the international market. According to Ezequiel’s insight into the capitalist World system it is the „good price“ as the only way to raise productivity again. Ezequiel suggests that a part of the project’s sales volume has to be invested in social programs like differentiated education for the children. The needs of Mother Earth did not come to his mind. At least not on this day.

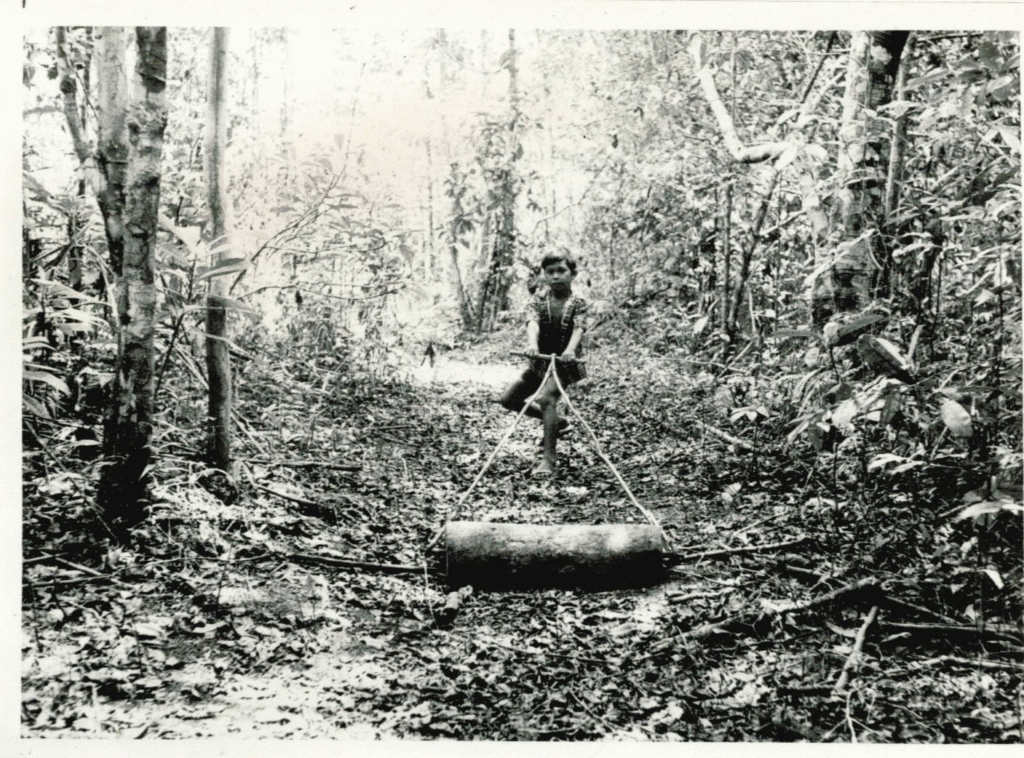

Damage done: the extraction of rose-wood (Tuxaua Sikú)

A few days before, we had met tuxaua (chief) Sikú, an elderly man confined to a wheelchair, who told us about the exploitation of rosewood. Rose-oil is an ingredient of the world’s most famous perfume Chanel no. 5, which was promoted by actress Marilyn Monroe, among others. However, tuxaua Sikú had another story to tell. Again he began with the „Golden Age“ of a diversified extractivism, the old days of selling forest produce (guaraná, andiroba, copaiba, low grade species of rubber like balaia and massaranduba, animal skins and more). It was crucial that this collecting work did not interfere with the subsistence cycle, since it occurred during the rainy season, when there was less work in the manioc gardens. In the 1950s and 1960s, river traders arrived demanding the exploitation of rose-wood which until then had no material or symbolic use for the Sateré-Mawé. With the help of chiefs, co-opted by corruption,a downright invasion of the Indigenous territory occurred, creating a predatory boom-and-bust cycle typical for Amazonian hinterlands. These enterprises usually concentrated on one product, exploited until it was literally extinguished (to extract the oil, rosewood had to be felled, the trunk cut into pieces, the wood shredded and boiled out). All over the territory illegal distilleries were built, which recruited Indigenous workers, disrupted social structures and encouraged prostitution. Men of most of the families worked for the river traders. The workers fell into debt bondage, because merchandise and food were sold to them at exaggerated prices; in the end they worked without getting any wage and were forced to work all year round to pay their debts. The damage was done: the subsistence cycle was disrupted, people went hungry and the enfeebled population fell victim to introduced illnesses. Since, according to tuxaua Sikú, pagés or shamans capitulated in the face of the health catastrophe, Western medicine, which slowly began to be introduced, was the only salvation. Finally, a faction of the Sateré-Mawé population opposed the intruders and managed to expel them. Again, the ecological impact of predatory extractivism – the extirpation of rosewood tress –was not an issue in tuxaua Sikú’s story.

Healing the damage: the forest gardens of the Sateré-Mawé (Kuitá)

In historical retrospect, Sateré-Mawé men conspicuously highlight their past as collectors of forest products and their (probably already pre-Columbian) tradition of being merchants, while downplaying the importance of gardening. Tuxaua Sikú described the forest as a source of marketable resources, but also as a sanctuary which protected people from epidemics. Even if the Sateré-Mawé experienced their share of social and cultural defeat, cosmological aspects continue to persist at least as a background noise to secular agency.

There are at least three mythical narratives that are actually cited within the wider context of commercializing forest products and political agency. One myth about a person called Grandfather Emperor (ase’i imperador) narrates the origin of colonial injustice, when the emperor takes along all the merchandise and factories to make them, while the Sateré-Mawé are left behind in the forest with only palm fruit. Beyond that, they are condemned to passively await sporadic benefits by the Emperor. Interestingly, this story of the origin of colonial dependency has been reframed by the activists of the Fair Trade project as a mandate to stewardship with the Sateré-Mawé as guardians of the forest. Second, Sateré-Mawé cosmogony tells of a place called nusoken, where an Animal Mother (miat ty) keeps the game and liberates it on demand of the shaman without expecting compensation. This structure of an unconditional mother-child-like relation seems to be behind the overwhelming, albeit socially and culturally disastrous success of public welfare programs (see Bird-David, 1990). The most obvious effect of (largely) unconditioned money transfers is the near paralysis of subsistence aggravating even more the already precarious food sovereignty (Kapfhammer and Garnelo, 2018). Finally, guaraná, which symbolically and ritually sits right in the center of Sateré-Mawé cosmology. According to the origin myth, the first guaraná shrubgrew out of the eye of a murdered child. At its grave the grieving mother Uniawasap’i prophesied the crucial role of guaraná in Sateré-Mawé society as a creator of social unity and harmonious life under an authoritarian, but benevolent chief (a guaraná beverage is ritually consumed during meetings to discuss and organize communal affairs). Leadership figures within the ambit of the project tend to justify their political aspirations with regard to this mythical background.

When Kuitá, proprietor of a particularly well-tended forest garden, talked to us, he largely stayed clear of political ensnarements and promises, but seemed to thrive on describing himself as a productive farmer (produtor) and leader of a group of young male and female gardeners in his community. Interestingly they all considered themselves as dyed-in-the-wool agriculturalists, quite different to the usual image as collectors and merchants. In contrast to an increasing number of emotionally disturbed youths in Sateré-Mawé communities who fail to connect with capitalist consumerism, as Ezequiel explained to us, Kuitá displayed an unswerving enthusiasm: “I am always happy when I meet with likeminded people. It is as if they were my kin.”

To paraphrase Anna Tsing (2015), against all odds Sateré-Mawé forest gardens make new life possible on colonial ruins. From an Indigenous perspective the transformative moment of reclaiming – mind the double meaning of this word – their forest territory can be found in the (re-)construction of Indigenous sociality and less so by a discourse on a diverse and sustainable ecology. However, the uplifting, forward-minded healing dynamics of Amazonian productivity little by little make the diverse sounds, colors, odors and tastes of the forest to (re-)appear.

Acknowledgment:

This research was funded by the LMU Sustainability Fund (2025), project entitled Nosology and Sustainability: Indigenous Healing Knowledge and Sustainable Human-Environment Relations in Northwestern Amazonia.

The interviews for this blog have been conducted by Wolfgang Kapfhammer and Ulrike Prinz during a trip to Sateré-Mawé territory in April 2025.

References:

Bird-David, Nurit. (1990). ‘The Giving Environment: Another Perspective on the Economic System of Gatherer-Hunters’, Current Anthropology, 31(2), 189-196.

Kapfhammer, Wolfgang, and Luiza Garnelo. (2018). ‘“We bought a television set from Lídia”. Social programmes and indigenous agency among the Sateré-Mawé of the Brazilian Lower Amazon’, in: Ernst Halbmayer (ed.), Indigenous Modernities in South Amercia (Sean Kingston Publishing, Canon Pyon), 131-62.

Kapfhammer, Wolfgang, and Gordon Winder (2020). ‘Slow Food, Shared Values, and Indigenous Empowerment in an Alternative Commodity Chain Linking Brazil and Europe’, Sociologus: Journal for Social Anthropology, 70(2), 101-22.

Tsing, Anna L. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton University Press).

[1] All names have been changed.

[2] Fundação Nacional do Índio, a government organization for „indian affairs“.

Cite as: Kapfhammer, Wolfgang. (2025). ‘“Nobody works out of love.” The healing force of Amazonian productivity’, Planetary Healing Blog, url: https://www.planetaryhealing.gwi.uni-muenchen.de/nobody-works-out-of-love/